With so many bad news going on in the world recently, it was difficult to get a positive balance out of the year 2020 when I tried to think about approaches for this article.

But then it struck me that next year, 2021, it’s actually the 10th year anniversary of my jump into the mobile casual game industry. And this is such a fast-paced industry that, even though it’s been only one decade, I feel like I’ve already made a few learnings that would be worth sharing here.

So, let’s start with one of the biggest cliches, but also the most dominant force that defines the reality we face as game developers.

1. Things in the industry change. And they do it fast.

When I joined 5 Ants (developers, between others, of Tiny Thief), it had only been three years since the App Store emerged. So it’s easy to imagine that a few things might have changed since then. But back in the day, it wasn’t actually as obvious to foresee what types of new challenges markets or technology were going to present to the studios that were making and publishing games.

For instance, even though it sounds funny when I say it nowadays, there was a time when the maximum file size allowed to upload games in the App Store was… 80MB, which seems like a joke if you compare it to today’s 4GB. In the studio where I was working before the App Store started lifting limitations, the developers had to make almost magic to make Tiny Thief’s animations play smoothly on devices. And it worked well. Not just well but also fantastically, since the game was nominated for the Annie Awards in the category of best animated game (we lost to The Last of Us).

But we weren’t the only ones. I remember other games that came at the time, like Beat Sneak Bandit, managed to achieve excellent graphic experiences despite the limitations, which some times makes me think that maybe nowadays developers are not making a very conscious use of people’s devices memories and limitations.

2. Good quality doesn’t guarantee success.

I think this is one of the toughest lessons I learned, and it came up pretty early too.

We all know that the App Store is a competitive market, but you do get what that really entails when you work with your team on an excellent game that gets a massive audience and critique success, and that eventually still needs to be removed from the App Store…

This type of thing also teaches you a lesson of humility and it allows you stay with your feet on the ground, but it also represents one of the hard parts of working in this industry. Trends are volatile, and the audience has lots where they can choose from. And you’ll always be subject to that.

3. The market can be unpredictable for good too!

On the bright side, some times success does reward hard work. I was lucky enough to join Wooga when June’s Journey was about to launch, which allowed me to witness in real time how the game evolved from being a hidden gem to the most successful title in its category (data from GameRefinery).

You always expect your project will be successful (otherwise, why would you be putting it out there anyways?). But seeing that actually happen is one of the most gratifying parts of the process, and a great motivator too.

4. This is like a science

This is a relatively new industry, and even though many of the disciplines involved in game development come from other older fields of knowledge, the particular use case of game development is not something we’ve add huge amounts of time to articulate as a solid scientific discipline with its own research and literature.

I see on a daily basis that we tend to stick to experience, references of similar cases , and feedback processes to know what’s the best for the products and experiences we are building.

Even though there is research out there we can not use for learning about our players, or to learn how to write good code, I can’t say that I usually find an abundance of materials that are applied to the development of video games.

We’re taking our first steps on things like qualitative research about player types or game UX theory, and showing efforts to apply scientific theories to game analysis of user tests.

Still, I’d like to see more about semiotics applied to game design (or which is the same, how does meaning emerge in games), or some sort of exhaustive methodology on game economy design.

5. A solid basic knowledge is one of the most valuable skills in a game designer.

A very important practice when it comes to improving your game design skills and your understanding of games in general will indeed be playing games. Every time I work with someone who shows an important baggage, I know they’re going to contribute with lots to the process. But that’s not all.

After having worked in several teams and with people with different degrees of experience, one of the qualities that always gives me more trust and inspires me in people is a solid understanding of the basics of the many areas of knowledge that are, in one way or another, involved in the craft: sociology, psychology, statistics, economy, art history, graphic design, history, maths.

Of course you don’t need to master all those, but you need, at the very minimum, the understanding of a high grad student. And these perspectives haven’t been useful to me in an abstract generic way, but in a very specific one. Nowadays I would say, before spending your edu budget on trying out yet another new game, or starting to learn how to program, take a course to refresh your statistics basics. Maybe you’ll miss out on some chats about the games that are trending, but you’ll also invest on your long term breadth.

6. The game designer doesn’t need to know how to do everything.

This point might seem to collide with the previous one, but the thing is: you need your breadth. It will help you understand how systems and rules work. However – you don’t need to do Everything.

It seems to me that the stereotype of the indie game developer that does absolutely everything in a project has defined some of the overall expectations on what a game designer is supposed to do in a project. Mind you, I’m not saying that you can’t do everything if that’s what you want, but you don’t need to.

I’ve been that person who does marketing, game design, customer support, and community management all at once and over years. And it’s been fun, it’s opened me doors, and let me learn quickly. But – Nowadays I know I don’t want to be put doing economy work or level design. It’s just not my thing and I don’t know how to do it as well as my colleagues anyways.

Do we expect from our cardiologist that tomorrow they’ll check our teeth?

I’ve seen in the last few years how companies and the industry overall are getting a more clear definition of the specialities of game design, and how the job offers are way more concrete. I like how that is giving us space to grow our skillset sustainably and to build trust within game design teams.

7. There’s nothing written about what the structure of a game team should be.

I have never been in two studios or two design teams that had the same structure. On the contrary, I encountered unique workflows in all of them. Even within the companies themselves, there were often different team structures for different projects.

Splits of responsibilities, sizes of teams, the way QA is integrated in the pipelines, the type of integration of localization and marketing teams, and the list goes on and on. I’ve been part of new teams, teams that were growing, and teams that were shrinking, and while structures solidify only throughout time, I’ve seen that very often the only way to know what’s the best way to shape a team is listening to experience, following an intuition of what can work, and trusting the people involved.

8. Premium is from Mars and F2P is from Venus.

I mentioned earlier how I’m seeing areas of game design (it’s also happening in all the other roles) specializing and becoming more concrete as times goes by. This is only exposing even more the fact that, if there’s something that characterizes this industry, that’s an outstanding variety in dynamics and processes.

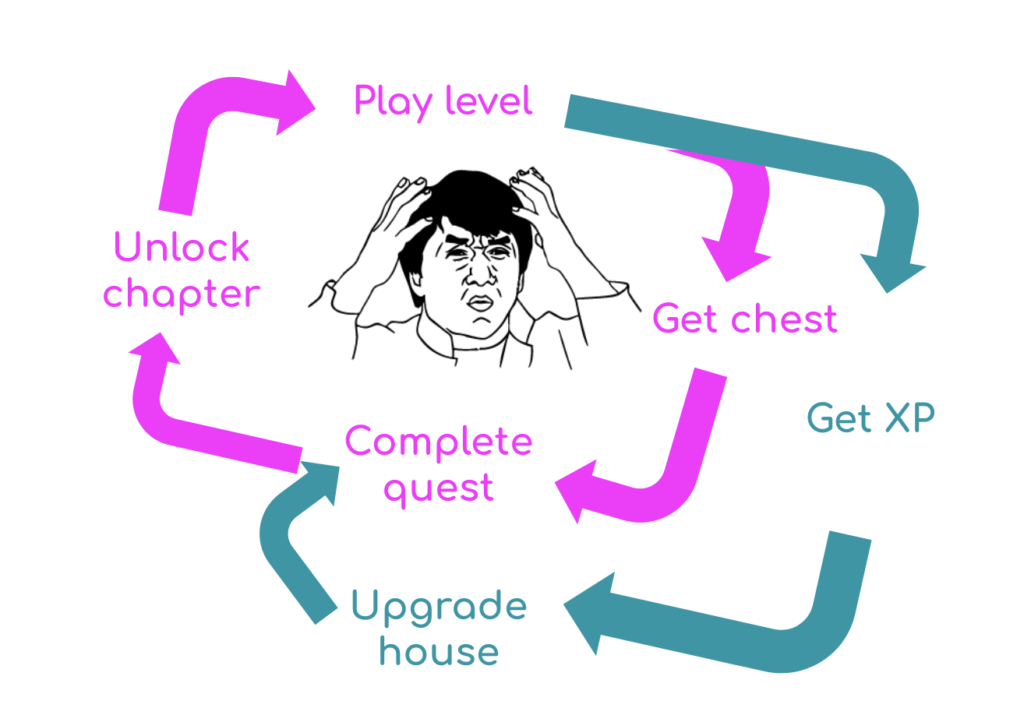

Another component that makes the ecosystem even more complex is the type of business model and platform. Even thought there are indeed lots of commonalities between design principles applied to different types of games (board games, triple AAA, F2P, etc.), there are also massive differences in all the processes involved: product management, art pipelines, marketing, technology used, type of audiences…

I stumbled across this when I made my jump into the F2P industry after years working in premium fire and forget games. If you’re curious about my specific learnings, you can check the slides of one talk I gave last year where I went trough some of the new processes and concepts I had to learn when transitioning from premium to F2P as a game designer.

9. It’s a small industry

Not that this changes anything, because all of us, regardless of the profession, should have excellent working ethics anyways, but it’s always good to remind yourself that you will probably work again with former colleagues.

Which is actually one of the fun parts about this industry, seeing how you come across old friends in the journey, which gives you a perspective that lets you see how much things change and how much you’re growing.

10. In this industry, you never know where you’ll be in a decade.

I studied marketing related degrees at a time and in a place where I was never exposed to the possibility to initiate a career as a game developer, and much less as a game designer.

I would have never thought that I’d be working in Germany as a game designers in a major F2P game company. I got here just following my intuition and my passion, and keeping my eyes open when opportunities showed up.

This in an industry full of new ideas and opportunities, but also dependant of lots of external factors. That means that things go fast, but also, that interesting things happen all the time. And I’ll be looking forward to see where this puts me in a decade from now.

Leave a Reply