Spoiler alert: This review contains massive spoilers, and comments on the game design of The Legend of Zelda Breath of the Wild (from now, TLOZBOTW). If you don’t want the story of the game to be spoiled, or your genuine experience playing the game to be adulterated with analysis and rationalization, stop reading now.

But if you want the subjective analysis of a game designer, developed over a period of two months, extensively described in a non-English native speaking but excited prose, and seasoned with an optimistic and casual tone, then in the name of the Goddess Hylia, keep reading!

I played TLOZBOTW for the first time about two and a half years ago. I was in the hospital waiting for a family member to give birth to a newcomer, and had a few hours to kill in my hands, so I thought it would be a nice opportunity to complete the game I had bought a year earlier but hadn’t started yet.

I didn’t complete the game that day in the hospital. What’s more, as I speak now, two and a half years later, I still haven’t completed it.

And the reason is that I thought I could just burn through the story, as in the other Zelda games I had played before, where, at any point in the game, you were where you were because that’s where you had to be. Then you just had to go forward, and at some point you would reach the end.

I’m talking about games like Twilight Princess, or the Nintendo 64 games, where the path ahead was always straight and clear.

In those other Zelda games, the narrative was strong and predictable. Which was part of the charm, to be honest. The village where Link lives; the Forest of Hyrule, where you will most likely get lost in one way or another; then at some point the town of the Goron; the Zoras; the Temple of Time where the Sword of Power lies; the Citadel of Hyrule Castle where it’s cool to buy from the shops; and of course at the end, Ganon. Depending on the game, many of these stages will vary, or not even be there. The order, too, varies. Then of course there will be other themes and locations, but all of it baked in a linear progression that connects beginning to end, and continues farther ahead into the future, until the next Zelda game, to be released a few years later. And then, repeat. It’s funny to think that throughout my life I have never not been waiting for a new Zelda game to come out. How many more times can one experience the same-ish hero’s journey and still get so much joy as to be there in line waiting at the queue when Nintendo comes back with the next Zelda game?

I don’t remember a Zelda game I haven’t loved. Excellent level design, immersive world building and heroic themes were always enough for me. Until I played a Zelda open world game.

But going back to the point of linearity, in all the other Zelda games I had played before, this hero’s journey, in all its splendorous and cozy predictability, was a big part of the charm for me. I didn’t quite assimilate what was going on in TLOZBOTW until I started playing the game recently, with the purpose of writing a review. Thinking about it, in hindsight, when the game first came up I noticed in the trailers and all that that there was something different about this Zelda game. To be honest, it felt quite dull. So much walking around and picking up mushrooms… What is heroic in that? Also… why is Link not wearing his green clothes? And where is Epona? And who will be the equivalent of Navi this time? I didn’t know much about open world games at the time either. So now you can approach Ganon literally from day number one? You can visit the Zoras before the Goron? Or the Goron before the Zoras, if you prefer? Also… the Sword of Power… it doesn’t come to you… YOU go to the Sword of Power.

I didn’t quite understand it the first time I played the game either. I got stuck in the first big boss, in the Divine Beast Vah Ruta. I had assumed I could just defeat him with what I had. Normally, in the Zelda games I had played, you collected the necessary weapons you needed to defeat a boss before encountering that boss. But it wasn’t the case then. And I got tired of trying, so I rage quit the game and found myself other occupation while waiting in the hospital, and didn’t play the game again in two and a half years.

I was just not ready for it.

Today I can say that when I play TLOZBOTW, I feel free.

Before going deeper into the topic of difficulty progression in this game though, I would like to illustrate the main difference between both approaches (linear vs. open world) with an example.

As explained in https://zelda.fandom.com, this is how you get the Master Sword in The Legend of Zelda Twilight Princess:

Before you get the Master Sword you must have saved Midna after Lakebed Temple, spoken to Zelda, and returned to Faron Woods. It is obtained by defeating the Skull Kid for the first time in the Sacred Grove.

Or in The Legend of Zelda Ocarina of Time:

Much like in A Link to the Past, the Master Sword is obtained by collecting the three Pendants of Virtue.

Or more intricately, in Oracle of Seasons:

The Master Sword makes a reappearance in Oracle of Seasons and Oracle of Ages, fittingly as the most powerful sword in the game. The only way to unlock the Master Sword is to have finished one of the games, and to have started a Linked Game on the opposite game. When a certain Secret in the game is found and told to Farore, she will upgrade the Noble Sword Link currently holds into the Master Sword. However, if Link still has the Wooden Sword, the Wooden Sword will become the Noble Sword, and the Master Sword will be found where the Noble Sword would have been.

When did being an epic hero consist mostly of crossing off the points in a checklist?

This is what I had to do to to get the Sword of Power in TLOZBOTW:

As I made my way into the north of Hyrule, I came across a woman in a stable that was talking about a legendary Sword of Power. From that moment on I knew what my destiny was. I remembered that in old Zelda games I had played the sword was normally in the forest, so I scanned the map looking for forest areas that I explored faithfully. At the same time I would of course do some other quests, some foraging, and whatever else I fancied. I met a traveler who said that he would be the one finding the Sword of Power. I felt butterflies in my stomach. That was just a random dude whose name and face I would quickly forget. I didn’t see him ever again. But the fact that I met him by chance made me feel like the chosen one. I knew I was going to get that Sword. I mean, of course I knew I was the chosen one that was going to get the sword. But when I was playing the game, and when I experienced this narrative, I also felt that I was the chosen one who was going to get the sword.

Refusing to look for the solution online, I looked for the sword in the Temple of Time (isn’t that where you find the sword in other Zelda games?), in more forests, forest-y areas, and at some point even in bushes. The Master Sword was nowhere to be found. At least, it wasn’t in the obvious (obvious for me) places, even though I was so ready for it… (I thought I was ready for it)… That was a weird feeling.

At some point I unlocked the map area with the forest. And holy moly, just looking at it in the map, if there is a place where the Master Sword was meant to be, that was it.

Then you go through the labyrinth, and finally, the test of power.

What? Do I actually need to do some test to get the sword?

And it’s not a skill-based puzzle. It’s not about trial and error. It’s about true heroic worthiness.

The next time I came back to the sword, that time I knew I was ready for getting the sword.

I knew it because I felt it in my stomach when I came back to the forest with my lastly acquired heart vessel, collected after endless traveling the world and much puzzle solving in Shrines after the Great Deku Tree had told me something like “You’re still not worthy of it – but – this time you were really close”.

That moment when I was pushing the A button harder than necessary, seeing how the health vessels depleted at an increasing pace, and my heart anticipated the image of Link raising the sword to the sky.

I certainly didn’t know how I was going to get the Master Sword when I started playing the game, and neither did the designers of the game or the writers of the Zelda wiki page.

But I got there at the moment that was right for me.

How difficulty progression works in The Legend of Zelda Breath of the Wild

The reason why I think this is the best Zelda game ever is because the promise and fantasy of this game (and the promise and fantasy of pretty much all Zelda games) rests on the most solid pillars game design could possibly lay to sustain them. The pillars of open world game design, and difficulty progression. To use another analogy, the game design triforce of TLOZBOTW has three parts that connect with each other in symbiotic and elegant balance:

- fantasy of exploration

- open world based level design

- difficulty progression

So let’s start talking about the fantasy of a Zelda game. Which is mostly a fantasy of exploring.

Exploration is, in its essence, the opposite of a linear experience. Besides, exploring consists, on an emotional level, of a mix of awe and fear, which is, in my opinion, the same formula that balances difficulty and fuels progression in this game.

You come across some enemies, and if you try you can beat them and maybe get some valuable rewards for it, but it might come at a cost. Your weapons might get broken. You might need to consume some valuable recipes. All in all, you might not even get a worthy reward.

There is a secret corner over there, or a deviation of the path, an usual shape in the mountain, that looks interesting. And you consider whether you should take just a step further and see what you find. You know that if you go a little bit too far, you might get stuck, or be defeated by an enemy, or run out of stamina and fall and get lost. But if you don’t try… how do you know if you will find the same spot again?

The tension emergent from the act of exploration is an essential dynamic generated by the mechanics and systems of TLOZBOTW, and paced by the difficulty progression.

One of the reasons why I wanted to talk about difficulty progression is because in TLOZBOTW, most of the numbers are hidden.

These are pretty much all the game state-related stats communicated with numbers:

- Durability of the effects of recipes and elixirs

- Armor resistance

- Attack of weapons

These are visible in the menu. When you’re playing the game, the only number the game shows is the time of the day.

On the other side, this is the list of game state-related stats that are not shown with numbers:

- Your health (although, this is indirectly shown with numbers, as in with “number of hearts”)

- Your stamina

- Your XP

- The XP needed to achieve the next level

- Your strength, skill, move, blah blah blah

- Armor resistance

The absence of player stats-related numbers in TLOZBOTW intrigued me from the beginning. I knew that the numbers had to be there, even if hidden to the player, and I also knew that the only way to get a grasp of them was feeling them while playing the game.

Hence, using my own player experience as my only tool I started playing the game with a question in mind: How is the difficulty progressing for me? How am I getting better in the game?

And the answer I came up with for that question is this one:

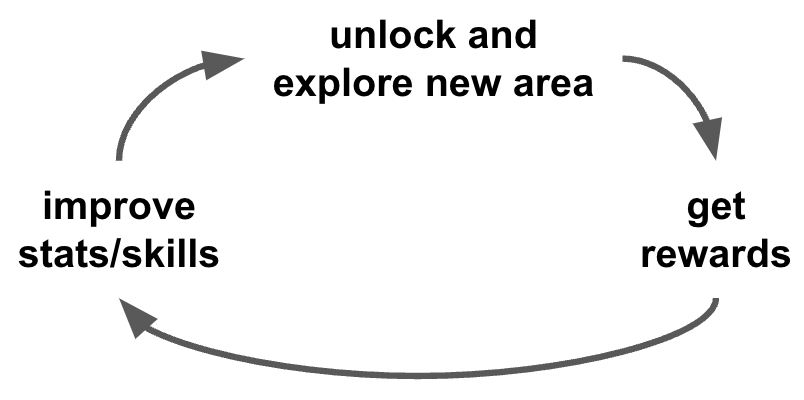

So the more health and stamina vessels you gain, the more towers you can access and the more areas in the map you can reach. And the more areas in the map you can reach, the more ingredients for your recipes you can collect, and therefore, the more boosts you can stock, and the more areas in the map you can reach. And so on and so forth.

The exploration and understanding of the world is the source of the energy that boosts your cycling in that loop. Which leads us to what the game is really truly about: Listening to nature, risk/reward assessment, and strategy forming.

“Listening to nature.” Now, that sounds cheesy you will say. But if you look around you in TLOZBOTW, you will see how the environment talks to you. The way in which the visual, level, and sound design generates meaning is where the magic happens.

The level design in the outdoors (non Shrines, and non Divine Beasts) areas is configured following Shigeru Miyamoto’s concept of “Japanese garden”, which is basically a way to represent space to make it easy and enjoyable to explore.

If you’re thinking about the real world, just walking around and being generally curious is not enough to have an engaging exploring experience. We know this because we’ve all been in nature at some point in our lives, and we know that when we’re out there, not everything means something. Not everything that is not accessible can become accessible. Not all the frustrating experiences bring learning. Not all the caves have interesting stuff inside. Not all the inhospitable spaces will hide a mysterious and precious reward. Real life exploration has just not been designed.

In TLOZBOTW, the space communicates and entices you.

The position of a tower and the geography of the area will show you the type of skill you’ll need to get to the top. The arrangement of a bokoblin camp will let you anticipate how difficult it will be to beat them. And so on and so forth.

The process of exploring never really truly ends. And it takes place at the same time as goal setting and strategy forming. A goal can be getting an ingredient, completing a quest, beating an enemy, just chilling, getting a nice view of the scenery, discovering a secret, you name it.

Once you get an idea of what you will need to achieve your goal, it’s time to do some risk/assessment and form a strategy. Do you have a strong enough weapon? Do you need to swap your armor to a more fitting one? Do you need to consume some elixir or recipe to boost certain stats? But also… and more importantly (but less obviously)… Are you ACTUALLY prepared deep inside your heart?

Let’s talk about emotional progression

It took me some time to put two and two together here.

But eventually, after much playing, after much experiencing, after letting go of the analytical side inside me, it came to me as an epiphany, that another way in which TLOZBOTW balances difficulty is with theming.

For quite some time I was scared of some of the challenges that presented to me in the game. I was scared of the blood moon. When the blood moon rose, I would just go to a stable, and take a nap to fast forward time. I was scared of the dark thick clouds surrounding Hyrule Castle, and I wouldn’t dare getting any close to it. Even the sole sigh of it dissuaded me. And above all, I was scared of the guardians, with their laser eyes targeting me no matter how far I was. Oh, guardians. They are bigger than you. They run faster than you. And what about that music that plays announcing their presence, always unnerving me in a primal way… I know this is a game, but still, the feeling is so clear!

My partner used the term “mental barriers”, and it clicked for me. When I think about them as “invisible walls”, which seems like an even more convenient term, I recall where they were in the game, and how throughout my game progression, at some points I managed trespassing them.

For example.

After I completed all the Divine Beasts and got the blessing of the ancient champions, I knew what I had to do. I saw myself running to Hyrule Castle, with the rattling sound of my upgraded armor announcing my arrival to my foes. With my Sword of Power glowing in my hand, prepared to seal darkness.

I, who had survived hardship, had died many times falling down cliffs and blowing up so many Remote Bombs on my own face. I, who had traveled from the bottomest of the land, deep inside boiling volcanos, to the coldest and most inhospitable peaks, today I can say that I am not completely vulnerable. I am not semi-naked and lost in a new unknown dangerous world anymore. Now I know many of the secrets of nature, and I know how to use them to my favor.

I went from this:

Poor, cold, and semi-naked. That’s how a true hero is born.

…to this:

more stamina vessels than he will ever need, and

even a mortgage!

There’s a snapshot that reflects my own personal hero’s journey. And it feels like my own because Link is an empty and generic (good-looking, sure, but still empty and generic) vessel I can fill with my own heroism, my own rhythm, my own narratives. He will become as strong as I manage to make him. Actually, it doesn’t even need to be a “him”. The variety of outfit designs, and the ability to customize their color gives us the option to characterize Link as an avatar farther away from the stereotype of the alpha male hero.

There is indeed a narrative established around the figure of a character with a background, but it’s bare minimal.

“Emotional progression” goes hand in hand with narrative. So let’s talk about how narrative emerges from gameplay in this game.

Hyrule is full of spaces that radiate meaning with different levels of intensity. From the ambiguity of open fields that seem too quiet and empty, to the strong and memorable genius loci of some grandiose landmarks, players are free to decide which path to take, and how they want to write their own stories.

As I try to explain the systems from which gameplay emerges in this game, I realize how difficult it is to rationalize its spirit in a way that pays justice. Still, the polish and the design is there.

The contrast between a trap of fog and death and the deepest and greenest forest. A transition between spaces designed for effect. The volume of the unnerving music fading out. The fog dissipating. A tiny bird (life again!) landing in front of you, and flying away in the blink of an eye. A few seconds of silence, and you’re not sure about what’s ahead. And then, after a moment of suspense, a different music starts playing, and you just know you made it. You arrived at the coolest place in all Hyrule. The cute little Koroks slipping away like leaves in the wind (I mean, not “like leaves”. They are actually leaves…). What the… Is there a Kokok Town in this game? Of course there is! A moment of revelation where suddenly everything makes sense in a different way. What a tease! Koroks here and there, Koroks populating literally every corner in the game, to the point where they become not much more than cute little dummy creatures to our eyes. And suddenly, it happens to be that they are the ones protecting the Master Sword in the place that I was searching with most anticipation. What a blissful discovery!

It’s just one more of the stories I experienced in the game.

There are potentially endless possible stories. Because TLOZBOTW is, above everything, a great branching story game. Can you think about a more exciting choice than deciding how you want to save the world?

Do you want to free up the Divine Beasts and get their help against Ganon? Or do you want to just go ahead and beat Ganon all on your own? Do you want to not to choose, and actually not save the world and explore it the way it is? Do you want to pursue the Master Sword and get your official “hero” title? Each of those paths will cross with different characters; make you face different challenges; earn different treasures.

Each player goes through their own journey in their own unique way. The only points in common between all of them is that they have a beginning and an end.

Which brings me… to the end. Like the real end.

How was the defeat of the evil power, the consummation of the hero’s quest, resolved in TLOZBOTW?

Let’s put it this way. Calamity Ganon is not by itself an example that you would like to quote as a brilliant boss design in game design theory. But I think it plays a decent role in its context.

I was actually quite satisfied with the whole “end” of the game (the Ordeal, if you want to stick to the story structure of the hero’s journey), as it contains two of the properties I value most when it comes to game design: simplicity, and adherence to the theme.

I mean… Your last interaction in the game, the move that will end with the evil power that has been devastating the world for centuries, is literally the shot of an arrow. Precise, powerful, synergized in a perfectly staged climax that feels natural and definite.

Speaking of the hero’s journey, as I was approaching Hyrule’s Castle with the purpose of defeating Calamity Ganon, I was wondering if there was going to be an “act III” (“the Ordinary World”). I knew that, realistically, that would have been nuts. Are they going to design a post-Ganon Hyrule just for the end game? Or even just for an end cutscene? With everyone celebrating, and welcoming you back. Hugging and toasting, and waving cute flags. Somehow that felt disproportionately cheesy. And inadequate.

Today, after completing the story, I take off my hat and applaud. In my opinion, by limiting the scope and keeping focus, the developers made the most out of their own design choice. In a way, not being told what else happens after Hyule finds peace, the idea that you will remain stuck in this apocalyptic world forever, left me with an enigmatic feeling. But also, going back to “the ordinary world” was the last of my desires after I defeated Calamity Ganon. What I wanted was going back to the game as quickly as possible, because to be honest, I wasn’t even remotely done with all the exploration that I wanted to do.

Difficulty balancing systems

That was quite a lot around difficulty progression! Thanks for sticking with me this far ^^.

So we said that it’s pretty cool how the player learns and engages with a space of endless opportunity in order to achieve their goals and get better in the game. But how does the game make sure that we don’t just burn through the content and lose interest?

One area I’ve paid attention to while playing the game is how certain game systems are there with the purpose of slowing down the speed at which the player cycles around the virtuous loops previously described.

Here I would like to talk about my two favorite rubberbanding systems in the game:

- the stamina system

- the paraglider (which can actually be seen as an extension of the stamina system)

A way to see how important these are is to think about how much of your gameplay time you’re engaging directly with these systems. A BIG PART.

The stamina system is great. It feels so natural. You barely realize it’s there unless you’re being analytical. The amount of stamina consumed is based on the amount of effort you make. Elegant design and intuitive mapping based on how human physical performance in the real world.

If you climb a wall horizontally, you use less stamina than if you climb it vertically. If you climb a vertical ladder, it uses a tiny little bit of stamina, but if you pause, it stops depleting. If the surface you’re climbing is almost vertical, you can run instead of climbing it, but you will burn through your stamina. Also, what about that “last effort” maneuver, when you’re reaching the top of a wall or a mountain, and you have just a bit of stamina left? Is it me, or does the system forgive the extra stamina you need if you jump at the right moment?

And of course, the moments of “massive effort”. Freezing in the air to shoot an arrow with impossible precision. It’s so overwhelming I feel tired myself.1

And all the communication to the player is done with character animations and a basic green circle; all the controls needed to engage with the system, based on a single button.

A bonus balancing system I wanted to mention is the weapons system, and specifically, the limited durability of weapons.

I’ve talked with people who hate this aspect, because it’s so frustrating when the weapons of your limited stock break. But this game wouldn’t be the same if weapons were unlimited, or easy to fix, or if they didn’t break. Fighting enemies would be too easy, and the other option I can think of, limiting the amount of weapons you can get, would make a very different game.

However, to play the devil’s advocate here, these are after all rational design justifications, and the truth is that game experience is not purely rational. I wonder if the designers of the game considered at some point that this could be such a frustrating mechanic for some players. They must have known. I mean, we all know that people don’t like losing things they own; even less if they owned them for a long time. This is called the endowment effect.

I also think another “mental barrier” here is originated by expectations defined by other games of similar genres. Some players will completely avoid encounters with enemies. Others will just deal damage with remote bombs, and turn combats into tedious chores. Others will stop playing completely, maybe because the game feels too difficult. And they might not even know why. That they had to use those good weapons to beat those enemies in order to get good weapons to beat enemies to get good weapons, etc.

You need to learn how the forces of the system work. For me it’s not clear how this is taught to early players really. Good weapons are not that easy to get at first. You don’t get enough of them to understand that there will be more of them. And therefore, you are reluctant to use them.

The UX does, to a certain degree, entice you to do so. Using weapons is REALLY cool. Their visual design, sound design, and animation design… You just want to use all the weapons with all the different attack movements over and over again because it feels so good. But I would find myself trying out my new weapons, then loading a previous game state so that they stay intact in my inventory, where they will remain as precious delicate treasures.

At some point I understood that I had to use my weapons if I wanted some gain though. And when you start using your weapons, the game just blooms for you. It’s more fun and it’s more engaging. You start noticing what effects each weapon produces on each type of enemy. You learn to use combat movements to avoid sucking all the damage and to avoid that your shields shatter at every turn. You learn that the number the weapon displays, damage, is not all the story. A big Claymore deals massive indeed, but in the time it takes you to draw it, your enemies will be done with you. So then you need to pay attention to the way enemies move and react.

I also quite like the “weapon placement design”. There’s something uncanny when you look around you and things look natural, but in a way it doesn’t feel natural. Because in the end, it’s been designed. You know a person put that weapon there. It’s not uncanny in a bad way necessarily. It feels mystical somehow. Mysterious. You know weapons are purposely offered to you, never just randomly placed in the scene via an algorithm. Because there is a story behind each weapon, the moment of loss is also meaningful. Sometimes even heroic. You know what the price for getting that weapon was. The stakes are higher.

For those of you still not convinced by these arguments in favor of the weapon’s limited durability… I personally think it’s worth it, even if it’s just because of how special it makes the Sword of Power feel. When I get a rare weapon I feel lucky; I feel powerful. But when I got the Sword of Power, I feel invincible.

But how difficult is this game anyways?

When talking about difficulty, one of the aspects to be aware of is subjectivity. Unless all the systems work with dynamic difficulty, the difficulty of the overall experience will be perceived differently by different players.

I reached out to some friends who had played the game asking about their perception of difficulty. Some people said that the game was too difficult and they churned for that reason. For others, it was way too easy. Based on the anecdotal data I collected it seems to me that for players who are used to open world games it is easier to understand the system loops faster, and therefore, starting off with solid steps. On the other side, players who are more used to linear difficulty progression, are more likely to be intimidated by the world (not just by the difficulty of facing enemies and puzzles themselves, but also by how indomitable nature looks!), and to just stop playing completely.

So in a way, as a player, you need to put on the level designer hat, and design your own progression in the game. You are the one who decides what to explore at any point. If meeting your goals is too difficult at a certain moment, hopefully there will be some joy in getting what you need somewhere else.

In any case, I realized when talking to my friends that everyone who continued playing the game always had stories, and that the difficulty progression and balancing defined to a large extent the way they engaged with the game generating those stories.

But now, going back to the original question.

It is more useful for me to think about difficulty in relative terms. When engaging with the different parts of the game and different points of progression, how far are players from their comfort zone? Are there enough systems in place so that they will get a challenging enough experience?

Looking at it from that lens I need to say that for me, the game started really difficult. After a few first attempts of defeating a Divine Beast and churning the game, I tried again a few years later, with more motivation and a more precise idea of how the game worked.

Then I started my real journey. I started making progress and getting better along a really shallow and long progression curve where I discovered how the world around me worked. And as I made progress, getting what I wanted started getting easier and easier.

Soon enough you learn that certain recipe ingredients populate certain areas of the map. You learn by heart the boosters you can get depending on how you combine the ingredients when you cook. For a while the pacing there was nice. I felt pretty much in the flow.

However, at some point, I got Rivali’s Gale ability, and that meant for me a dramatic decrease in absolute difficulty.

Until that point I had barely unlocked half of the map. The remaining towers were either too much of a pain in the ass to conquer, or just virtually impossible. Now I could just lazily burn throughout them. Powerful enemies at the bottom of the tower that would kill me with the blink of an eye? Just jump past them. Guardians, which I was still too weak to beat and too slow to run away from? Hop! Just shoot yourself to the sky. Running out of stamina? No need for that anymore!

With Rivali’s Gale you can get mostly anywhere you want. And you have an inventory of three jumps!

I remember how, when I unlocked a new tower the first few times, the experience felt special and memorable. But at the end, I found myself wishing I could just skip the cutscenes of the unlocking sequences.

It made me feel as if I was cheating the game. Shipped high into the sky, from where I could see the obstacles around the towers, which had been meticulously placed there to challenge my skills.

Another point where the difficulty ramped down for me was when I got the Master Sword.

I guess mostly because I felt like a badass hero with it, but also, it does give you an advantage against the Guardians and final bosses.

Which brings me to the topic of…

Final bosses.

They easy. I think mostly because of how simple their AI is. Once you go through a couple of them, you can quickly parse some winning tactics:

- Deflect their attacks, either dodging, or deflecting them with your shield (if they take the form of projectiles). This will stunt them.

- Deal critical damage. You can deal great amounts of damage if you use the Master Sword or if you use a weapon with the elemental power the boss is vulnerable to, which is pretty easy to guess (I mean, you just need to read their name…).

- If they get you, they might deal decent damage to you. So either get good armor that’s resistant against their element, or an elixir, or just practice a couple times until you develop some muscle memory in reaction to the attack animations.

- Sort out what the weak spots are (normally an eye). Arrows will help you hurt them with precision.

- Sometimes using a specific Sheikah Slate power against a specific boss can be crucial too.

Once I practiced and mastered these, it got pretty easy. Surprisingly, Calamity Ganon worked the same way (plus he was already half done when I faced him, cause I had some good friends helping me).

So well, that was it. After a bit I was pretty much done with all the Divine Beasts and all the evil bosses everyone wanted me to finish. What is a hero to do then? Was my hero’s journey over? Not at all! There were still lots of challenges and quests waiting for me, virtuously spread around the land. I just needed to search for them. Labyrinths, shrines, Lynels, horse riding, rare weapons and armors, secrets the hylians have teased me about, and much much more.

And if all this becomes too easy for me one day, well, I can always try to complete the 100% of the game! Or get those shiny DLCs and unlock master mode! Or go…

Back to the origins

Eventide is a refreshing titbit of level design where Link needs to fight enemies and survive in the wild as naked as the day he was born.

In this level you’re suddenly stripped of your weapons and other overpowered equipment, which instantly changed the way I perceived and moved in the environment. Whereas at that point in the game I was easily brute forcing my way and bulldozing most of the enemies I was encountering, suddenly I had to pay attention to every step I was taking, measuring my actions and the risk involved. It must be similar to the feeling our ancestors experienced when they explored nature! Your senses need to be extra tuned. Listen carefully to the sounds around you, look at what’s in front of you. An invitation to, once more, put on that level designer hat, and try to explore other locations of the game in a more mindful way.

Following this inspired feeling, I did this exercise of mindful exploration where I went on to explore the snowy region of the Hebra Mountains.

I just assumed that there must have been something of interest at the peak of some of those mountains. This was my route:

If you look at the map, you can see the elevation of the areas, and in this case, the position of the Hebra Trailhead Lodge is really inviting as a point of arrival.

I love how they walk the extra mile there, and they placed this little narrative in the hut, where you feel like you’re following the steps of a traveler who went through the same path before you.

Some elements like the sign, the ladder, or these skull torches define the boundaries of the area:

In the end it happens to be that more than climbing, you’re doing some hiking or trekking after all, but off we go!

The design of mountain areas is a perfect example to illustrate how the forces of the environment drive you in different directions. I saw this flag waving in the distance, and then I knew I had a goal, even though I would need to face several perils along the way.

As I go higher and higher up the mountain, the cliffs become natural edges. The fog entices and intimidates me at the same time. My level of uncertainty depends on how much it obscures my visibility. The atmosphere is eerie.

The flavor of navigating this area resonates in themes like: uncertainty, hopelessness, loneliness.

When I get to some strategic points, like the top of the mountain, I get what Christopher Totten calls reward vistas, a very common type of reward in TLOZBOTW, where one can appreciate particularly impressive landscape views like these:

The contrast between the different ways in which the weather affects the visibility of the scene (seen in the last three screenshots) produces a sense of discoverability.

In TLOZBOTZ these reward vistas are not just beautiful landscapes, but environments that tint the gameplay experience with different emotions.

I made my way to Talonto Peak, which was crowned by this tree, thinking that there would be some secret hidden in it, a Kokok perhaps.

But no matter how much I climbed, I found nothing. Can’t take anything for granted.

Moving on to my next goal. I identified another peak in the map, the Hebra Peak, that seemed promising. This time, when I reached it, I got my reward!

But also, a little bit hidden underneath the peak…

Another concept that Christopher Totten defines in his book An Architectural Approach to Level Design, that is used very often in TLOZBOTW for enticing the player, is the idea of “reward denial”. Shrines are often integrated in the environment following this principle.

The reward (in this case, a Shrine), is there; I can see it, but it’s not granted to me. I need to claim it using my wits. I overcame these glaciers (in the previous photo) paragliding over them, but once I was at the other side, I realized that I still needed a way to remove the ice that was covering the Sheika Slate access.

The predominance of certain types of materials in the area doesn’t just make the landscape in this game more rich and immersive, but they also generate fun systems and mechanics (what the developers of the game called “material design”). As you learn about the physics of the materials the environments are built with, you also start understanding what they tell you about the difficulty of the area, the rewards that populate it, and the general role they play in the progression of the game. In these snowed mountains for instance, the physics of the interactions between cold and hot are used constantly for clever level and puzzle design.

But going back to our little day trip, since everything that goes up must come down, the last part of my hike takes a fun turn with the discovery of this secret door down at the bottom of a slope:

I can’t seem to open it using my Sheika Slate, so I inspect the surroundings in detail, until I notice that the marks on the ground in front of the door have something peculiar in them.

They seem to mark a sort of path, which I trace uphill until I arrive at a flat area with some random snowballs lying on the ground. I had seen those snowballs when I was exploring before, but I had completely dismissed them. Now it clicked for me. It was time for snowballing!

And thus I opened my way into another Shrine. The last discovery of my alpine adventure.

What’s next

This article doesn’t even cover a small fraction of what there is to say about difficulty progression in TLOZBOTW. I limited my comments to the areas that were relevant to me during my player journey, but I am aware that there is much more about it. Some people brought to my attention hints of dynamic difficulty in the game, like some types of enemies that only appear after you have killed a certain amount of them. I left that out of my article because I didn’t notice or experience it, and I wanted to stick to my own understanding about the game as part of my learning exercise.

There are also other aspects of this game that I would like to think about and write about one day. The puzzle design of Shrines and Divine Beasts, the onboarding, or how the environmental design builds the world of apocalyptical Hyrule. But for now, I shall rest.

As I was writing this article, the trailer of the next Zelda Breath of the Wild game was released. Nintendo called it Tears of the Kingdom, but people are calling it Breath of the Wild 2. I was relieved to see that the “sequel” is based on the same open world concept, and that actually (!) they’re using the same map of Hyrule. Deep inside my heart I was hoping that they wouldn’t design a different game. All that is needed, I think, is more content, more levels, more mechanics. In my dreams, from now on, Zelda becomes some sort of game as a platform. Because I can’t see how any other Zelda game could deliver the fantasy in a better way than Breath of the Wild did. Breath of the Wild is what all Zelda games always wanted to be.

I am happy that they made this game. I remember many many years ago, when I was considering whether to buy the Nintendo Switch or not (I was jobless at the time), a friend told me “Zelda Breath of the Wild is like a course in game design”. It was also a time where people thought buying a Switch was a bad investment because there weren’t enough good games coming out, so by extension, The Legend of Zelda Breath of the Wild was like a very expensive course in game design.

Today I look forward to the release of The Legend of Zelda Tears of the Kingdom. There are some questions popping up in my head though. Like, how are they going to design a good difficulty progression? Will the design be articulated around the hero’s journey again? Won’t it feel too trite for those who played Breath of the Wild?

Will koroks look the same or will they look different? What about Shrines. Will they even exist? And actually… how will everything that is part of TLOZBOTW look and feel in this new game? What will be the time period when the story will be set? Apocalyptic? Post-apocalyptic? Pre-apocalyptic? A time of peace and happiness?

I am sure that the designers of Tears of the Kingdom will challenge assumptions and break conventions to bring the craft of game design to the next level. Until then, I will keep dreaming about my future journeys in the land of Hyrule.

Last words and acknowledgements

If you went through all this babbling until here, that must mean that you really care about game design, and therefore I invite you to take some time to share your thoughts in the comments section.

Also, if I have included in this article some wrong assertions resulting from my bad memory or even from a place of ignorance, I apologize.

Finally, I want to thank some people and sources of inspiration that supported me while I was doing my research.

My boyfriend, who was playing the game at the same time as me, and shared his experience with me and engaged with me in large conversations around every little aspect of the game. Apparently, design spoilers really trigger me, so he also had to deal with my anger every time he was bringing up a mechanic or puzzle that I hadn’t experienced yet.

Then also my colleagues at work, who had to put up with my random apology of Zelda for a couple months; and my Linkedin contacts, who responded to my questions, giving me perspective.

Finally, I wanted to mention one of the main guides of my analytical thinking while I was playing the game, Christopher Totten, who wrote An Architectural Approach to Level Design, a book that made me start thinking about games in a different way, and I think every game designer should have in their bookshelf.

And of course, thanks to you, my dear reader! I hope you enjoyed the read, and that you will be back soon to read my next review!

Happy end of the year!

Foot notes

- By the way, how cool is it that the ultimate “test of stamina” in the game is not measured with stamina, but with hearts.

Leave a Reply